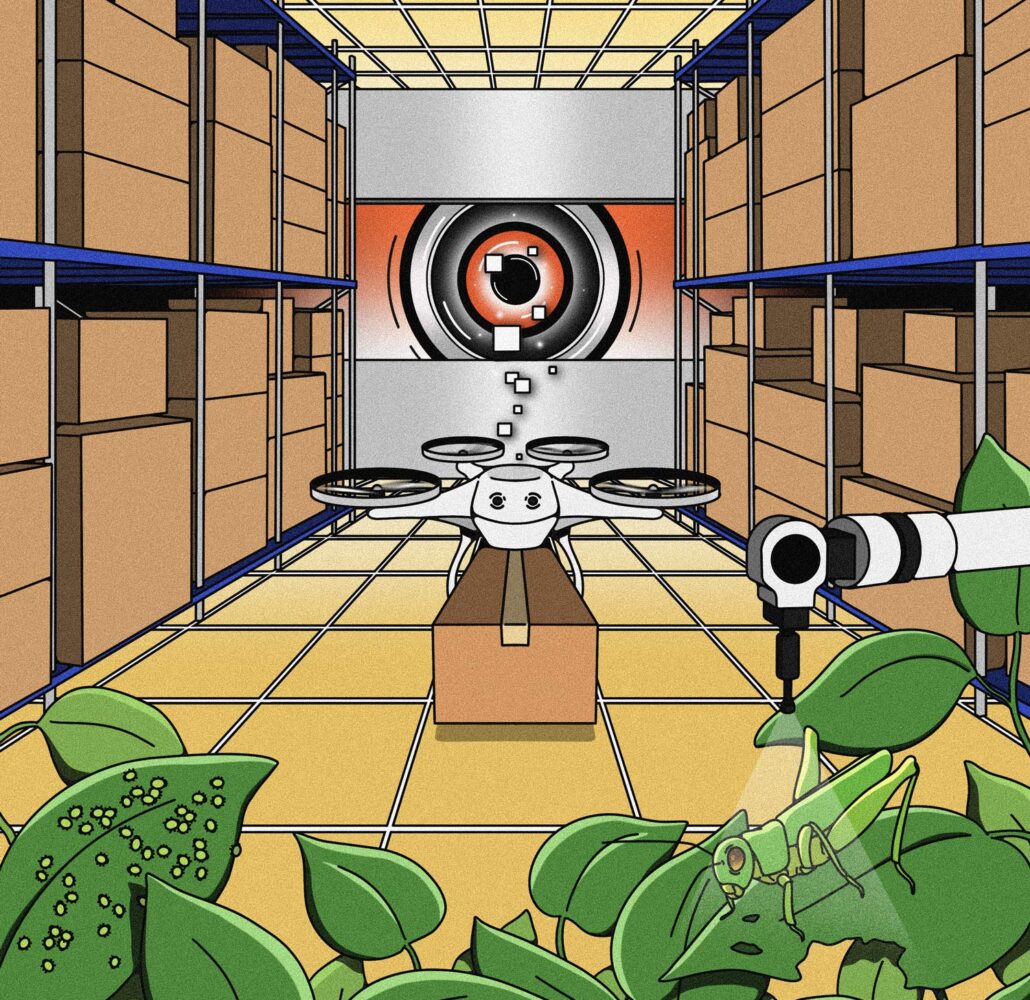

Imagine robots that can spot crop pests, drones that navigate warehouse aisles without GPS and machines that can see and understand the world as we do.

At TMU's Computer Vision and Intelligent Systems Laboratory, Computer Science Professor Richard Wang is turning these possibilities into reality by giving machines the power of sight.

"If you really want robot intelligence, you have to let it see," says Wang, who leads research in computer vision at TMU.

His research is already transforming agriculture and warehouse logistics through practical applications of AI that can see and interpret visual information.

"Images contain a lot of information," he says. "Enabling AI to interpret what it sees can become a very powerful tool."

Robotic pest patrol

One real-world application of Wang’s computer vision research is revolutionizing farming. A few years ago, Wang teamed up with researchers at American universities, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Science Foundation to tackle one of agriculture’s biggest problems: pests.

Every year, pests destroy up to 40 per cent of global crops, worth an estimated $US70 billion.

Controlling insect populations requires around two million tonnes of pesticides each year, which contributes to pollution and can harm wildlife and people.

Wang and his fellow researchers used deep learning models and computer vision to enable machines to spot aphid clusters in sorghum fields.

With this knowledge, robots can patrol fields and detect infestations.

“Once an infection reaches a certain level,” he says, “a sprayer on the robot can target and apply chemicals to infected areas, rather than spraying the entire field.”

TMU computer science professor Richard Wang said that about 25 years ago, progress in computer vision was slow - but today, conferences on the topic attract thousands from both academia and industry. Photo by Sarah McIntyre.