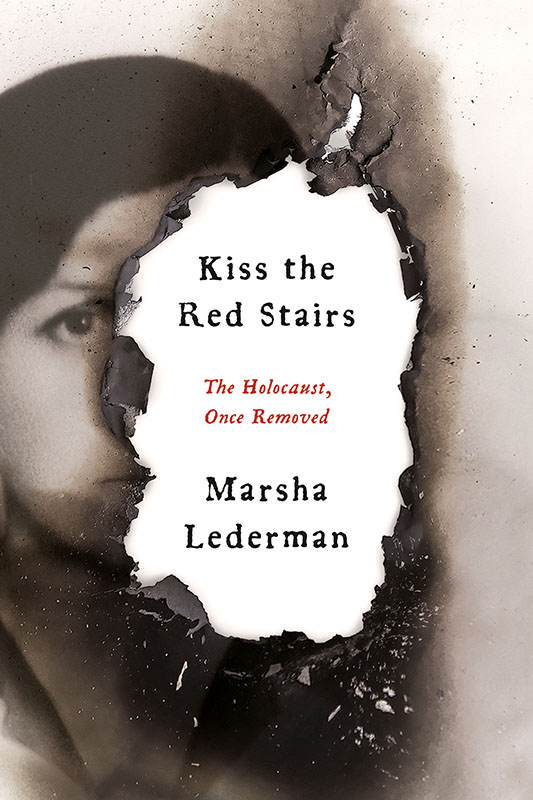

Award-winning journalist for The Globe and Mail—Marsha Lederman, Radio and Television Arts '88, decided to look towards her family for her next big project. Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed is a captivating memoir which dives into her parents' Holocaust stories and examines how intergenerational trauma may have shaped her own life and experiences.

In this extended version of the Q&A with Marsha, we discuss the motivation behind the book, how the research brought her closer to family, and what she learned about her parents along the way.

HF: What motivated you to start writing?

ML: I was curious about intergenerational trauma and epigenetics since this field seems to explode. I was going through some personal stuff at the time and started reading a lot about it and realized there was probably something to be explored there. Sure, there have been lots of memoirs about the Holocaust and children of survivors of the Holocaust. But I was interested in that particular aspect of intergenerational trauma. Whether epigenetics—the science—has played a role in any issues I might have experienced in my own life. So, that was what started the deep research into the area, and then at some point, I just started writing stuff down, and I thought, I think I've got a book here.

HF: What did it feel like to write this book?

ML: Sometimes I’ve felt comforted learning these stories about my parents, and other times, it was difficult and lonely. There were different kinds of research—the research I was doing into my family’s story was sort of comforting. But the research about the death camps and what people experienced was brutal, because I’ll never know what happened to my grandparents. I pictured them in these circumstances, which was absolutely shattering for me.

HF: Did this research give you a greater understanding of what your parents experienced?

ML: I learned more about my parents, but not necessarily because of what they experienced but because forcing myself into this zone where I thought about them a lot led me to feel a level of closeness and intimacy with them that I had not felt before. Being immersed in them while writing gave me so much admiration for them and made me very protective of them.

HF: Did you have any practice that would help bring you back to the present so you weren't constantly dealing with the trauma and grief you had to process while writing?

ML: The heart of the work was happening during the pandemic, so I didn't have the same outlets I might have had otherwise. I'm a pretty social person. I have people over to my house all the time. So, I probably would have had a lot of friends around if I had travelled, or I would have gone to the spa or something, but I couldn't do any of those things, so it was a lot about being with my son and being in nature, as I found nature incredibly healing.

And I was also connecting with people either by zoom or facetime online. I spent a lot of time talking to my sisters for the project, which was a beautiful thing. It turned out to be really nice to connect with them and talk to them much more often than I usually had. And so it was forcing myself to be present; that was the key.

HF: Did you learn anything new about yourself or your upbringing when you reflected on things to include in the book?

ML: I think I was mainly able to bring a new perspective to what life was like for my parents to have three children after what they've been through. Doing this research and listening to the stories and meditating on what my life had been like, I think, helped me understand what they had faced, and it made me a more sympathetic daughter than maybe I had been previously.

They both died before I became a mother, so that is a huge regret. I think once you become a parent, all sorts of things come to mind about your own parents that you might never have thought of, so I never got to have that chance to, you know, thank them for the sleepless nights. Parenting is hard, no matter what; it's tough when your whole life has been trauma and grief—which was their experience.

HF: You review books and various art forms for a living, but now you're on the opposite end. What was that transition like for you?

ML: I try not to think about the book being reviewed (laughs). This is the first interview I'm doing for the book, so it's interesting being on the other side of it. I think the best way to become a writer is to read everything you can get your hands on, and I'm in the incredibly fortunate position to read and write about what I'm reading for a living. So, I think having access to many great books and constantly reading and interviewing authors has helped me. I believe every person, every artist I've interviewed, has somehow helped me in my art, even if it's just a tiny little minuscule thing. So, all of that has helped build me up into someone who felt I could write my book.

HF: Can you think of one message you hope readers will take away from your book?

ML: Talk to your parents, talk to your grandparents if they’re alive and get the stories down while you can. I also hope that there’s an uplifting aspect to the book, that no matter what happens to you in your life—there is some light and there can be rebirth in some way. Maybe it’s in unexpected places, so try and find that.

Want to know more? Visit our Lifelong Learning page online and watch the Book Talk Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed.