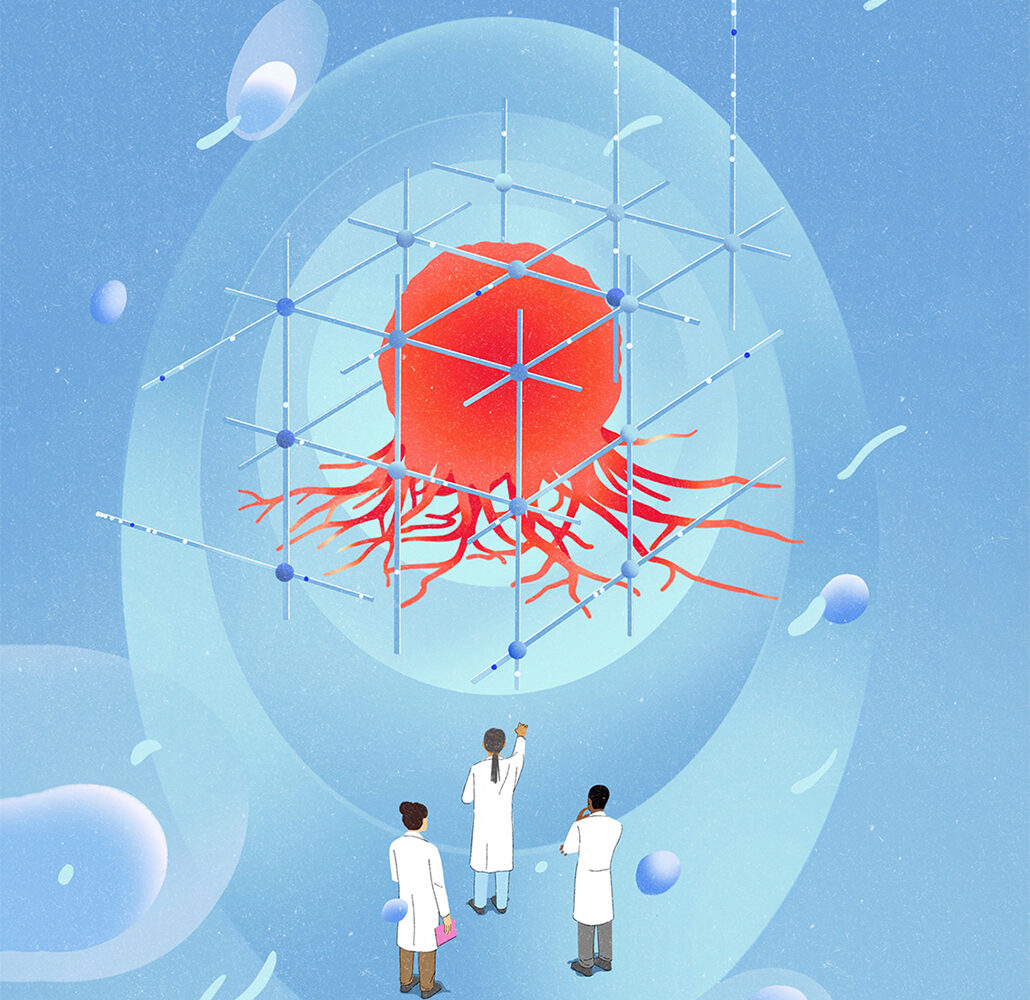

Mathematician Kathleen Wilkie’s research aims to open a door to better outcomes and quality of life for people with cancer, through math modelling and computer aided numerical simulations.

“I use math to help understand how a patient’s body is going to respond to the disease and the therapy they choose. Everyone’s body is different and to achieve better outcomes for more patients, cancer treatment needs to be personalized to address the whole patient,” says Wilkie, a professor in the Department of Mathematics, in the university’s Faculty of Science.

One of the greatest challenges in cancer treatment is to figure out why a specific treatment works for some patients with the same type of cancer—such as breast, prostate or colorectal cancer—and not others, and predict who will benefit to help choose the right therapy for each patient.

Cancer survival rates for Canadians have risen to about 65 per cent today from 55 per cent in the early 1990s and 25 per cent in the 1940s, but treatment still fails for 35 per cent of patients. Wilkie hopes her research will improve those odds further.

“We’re trying to better understand the heterogeneity of populations and use models as virtual clinical trials to help identify which patients would benefit from a type of treatment and which ones should avoid that specific treatment because it would be pro-tumour rather than anti-tumour,” explains Wilkie.

“If we can avoid giving a patient a treatment that’s not going to work for them, we will improve their quality of life by avoiding an unnecessary treatment phase, and possibly suggest another treatment that could provide a better outcome.”

Personalizing treatment

Wilkie is using her methods to help identify personalized treatment options to address cachexia—a dramatic loss of muscle and fat tissue that is a common condition developed in certain cancer types and an unintended side effect of certain chemotherapy drugs. It’s a debilitating condition that may lead to the patient feeling too unwell to proceed with treatment.

In a recently published study, Wilkie’s model simulations quantified the effects of many different chemotherapy dosing schedules on lean body mass and tumour control.

“We used our model to identify potential drug dosing schedules that can preserve lean mass better than others and still shrink the tumour,” she says. In future, this specificity around different treatment regimens on cachexia could give patients more agency.

“Low-dose, high-frequency schedules might be chosen in palliative care settings, for example, where cancer remission is no longer an option, so the goal then becomes reducing pain and increasing quality of life,” says Wilkie.

To further personalize treatment choices, Wilkie will use math models to look at how individual differences in factors such as age, body composition, gut health and immune system health influence muscle wasting risk in response to the cancer and the treatment.

“My vision would be to make more measurements about the person’s whole body and integrate this information into patient-specific treatment planning, including dosing schedules,” she says.

In a journal article in Mathematical Medicine and Biology, Wilkie’s math modelling simulations showed another promising application: anti-inflammatory treatment at the time of surgery inhibits a pro-tumor response.

“As more data and models are generated to show the influence of inflammation on cancer growth and progression, prescribing anti-inflammatory drugs during and after surgery may become the standard of care,” she says.

For Wilkie, developing more treatment options for cancer patients that address cachexia is both a scientific and personal priority. “It’s very satisfying to do research that has the potential to help cancer patients reduce a condition that is painful, exhausting and worsens their quality of life.”