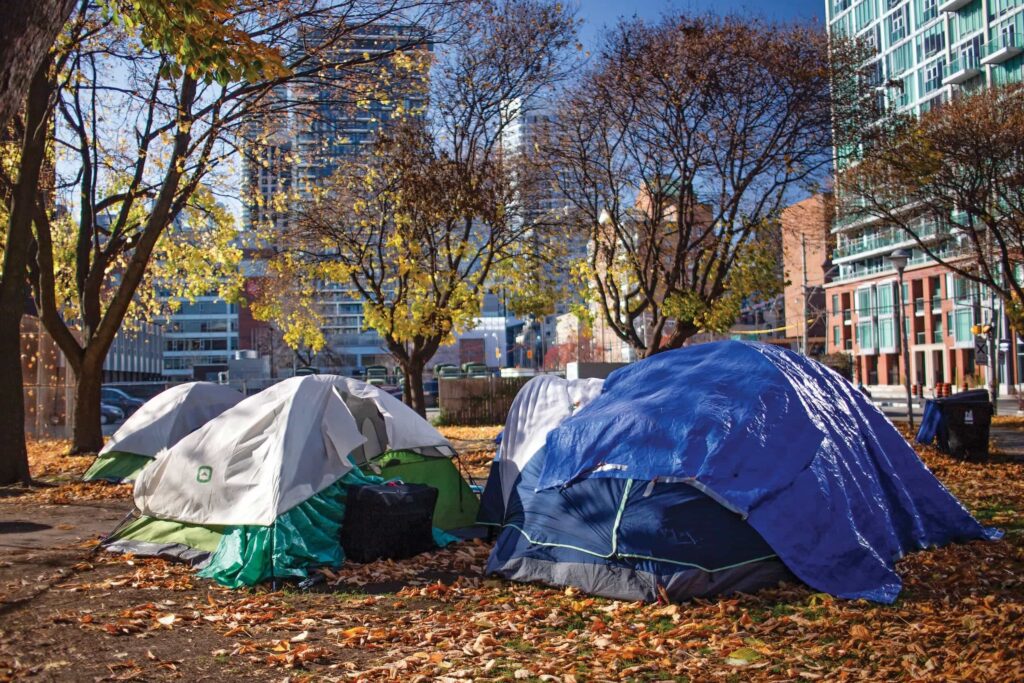

Still facing COVID after more than a year, advocacy organizations, city planners and frontline service providers are now looking ahead to picking up the pieces. COVID has shone a light on the city’s desperate need for housing and shelters. We need schools with better ventilation systems, educators to make up for gaps in learning due to closures and to address classroom sizes. We need long-term care facilities where care workers aren’t stretched to their limits. We need food programs, as the cost of everything continues to trend upward. And we need to address racism head-on.

The inequities laid bare by COVID are not new. Health inequities have always been with us. “We know about poverty and diabetes, we know about maternal experiences of racism and infants with low birth weight,” says Josephine Wong, a registered nurse and professor of nursing at Ryerson who specializes in urban health. That it’s only when the health of more affluent people may be at risk that we pay attention to the health of low-income marginalized people “makes me really sad,” says Wong.

Pamela Robinson, director and professor in the School of Urban and Regional Planning at Ryerson, says that while “equity-deserving communities have long known about and directly experienced the growing disparities and underfunding … a wider range of people outside of those communities are starting to understand, in quite specific ways, where we have failed to meet the needs of all community members. I think the big question is, ‘what change will follow?’”

“We need to build more inclusive communities and put forward more inclusive policies, most pressing of which is adequate housing and safe water for Indigenous Peoples.”

—Josephine Wong

Josephine Wong, registered nurse and professor of nursing at Ryerson. Photograph by Nation Wong